Gyotaku Unveiled: How Japanese Fish Printing Blends Art, Nature, and History Into a Timeless Practice. Explore Its Origins, Techniques, and Modern Revival. (2025)

- Introduction to Gyotaku: Origins and Cultural Significance

- Traditional Techniques: Materials, Methods, and Mastery

- Gyotaku in Japanese History: From Fishermen’s Records to Fine Art

- Contemporary Artists and Innovations in Gyotaku

- Gyotaku in Museums and Educational Institutions

- Technological Advances: Digital Gyotaku and Preservation

- Environmental and Conservation Aspects of Fish Printing

- Global Spread: Gyotaku’s Influence Beyond Japan

- Market Trends and Public Interest: Growth and Forecasts

- Future Outlook: Sustainability, New Media, and Evolving Practices

- Sources & References

Introduction to Gyotaku: Origins and Cultural Significance

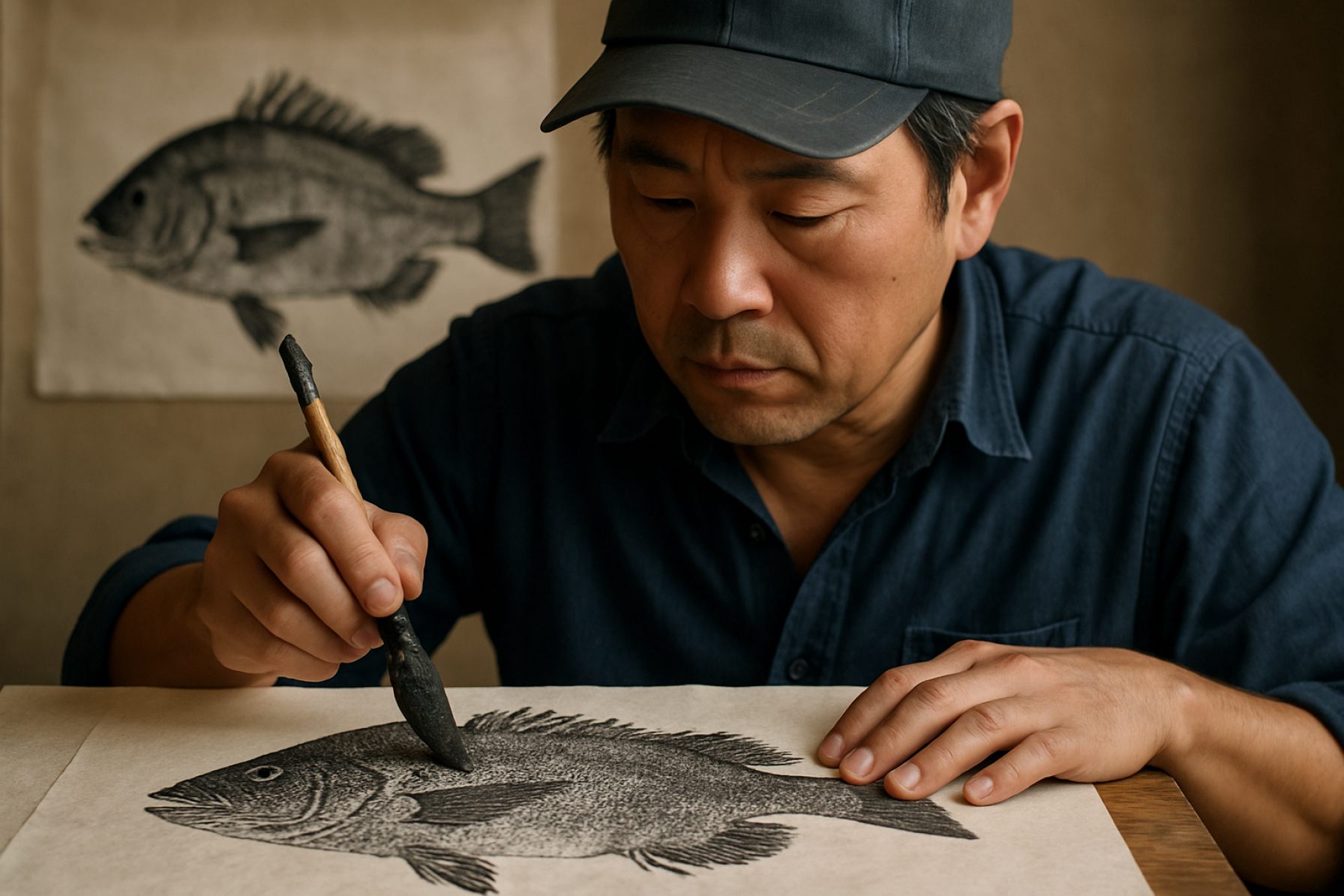

Gyotaku, which translates literally to “fish rubbing” in Japanese, is a traditional art form that originated in Japan during the mid-19th century. This unique practice involves making inked impressions of real fish on paper or fabric, capturing not only the physical likeness but also the intricate details of the fish’s scales, fins, and features. The origins of gyotaku are closely tied to the fishing communities of Japan, where it was initially developed as a practical method for fishermen to record and commemorate their catches. By pressing a freshly caught fish onto rice paper and applying ink, fishermen could create a precise and lasting record of their prize specimens, serving both as a memento and as a form of documentation for competitions or personal achievement.

Over time, gyotaku evolved from a utilitarian record-keeping technique into a respected art form. Artists began to experiment with different materials, inks, and compositions, transforming simple fish prints into elaborate works of art. The process typically involves cleaning the fish, applying sumi ink or natural pigments to its surface, and then carefully pressing paper or fabric onto the fish to transfer its image. Some artists further enhance the print by hand-painting details or adding calligraphy, blending scientific accuracy with aesthetic expression.

Culturally, gyotaku holds a special place in Japanese heritage. It reflects the deep connection between the Japanese people and the sea, highlighting the importance of fishing in both daily life and spiritual practice. The art form is also closely associated with the principles of respect for nature and mindfulness, as it requires careful observation and appreciation of the fish’s form. Today, gyotaku is practiced not only in Japan but also internationally, with artists and enthusiasts adapting the technique to depict a wide variety of marine and freshwater species.

Gyotaku is recognized and promoted by several organizations dedicated to preserving traditional Japanese arts and fostering cultural exchange. Institutions such as the Japan Foundation play a significant role in supporting exhibitions, workshops, and educational programs that introduce gyotaku to global audiences. Museums and cultural centers in Japan and abroad often feature gyotaku in their collections, underscoring its value as both a historical record and a living art form. Through these efforts, gyotaku continues to inspire appreciation for marine life and Japanese artistic traditions well into the 21st century.

Traditional Techniques: Materials, Methods, and Mastery

Gyotaku, the traditional Japanese art of fish printing, originated in the mid-19th century as a practical method for fishermen to record their catches. Over time, it evolved into a respected art form, blending scientific accuracy with aesthetic expression. The process of gyotaku is characterized by its meticulous techniques, specialized materials, and the mastery required to capture both the physical detail and spirit of the fish.

The primary materials used in gyotaku are natural fish, sumi ink, washi paper, and brushes. Sumi ink, a carbon-based black ink, is prized for its deep, rich tones and ability to capture fine details. Washi, a traditional Japanese paper made from the fibers of the mulberry tree, is favored for its strength, absorbency, and subtle texture, which together allow for precise ink transfer and durability. Some artists also use silk or cotton fabric as an alternative medium, expanding the possibilities for display and preservation.

There are two principal methods in gyotaku: the direct (chokusetsu-ho) and indirect (kansetsu-ho) techniques. In the direct method, ink is carefully applied to the surface of the fish, and a sheet of washi is gently pressed onto it, transferring the image in a single impression. This approach demands a steady hand and acute attention to detail, as the pressure and placement must be exact to avoid smudging or loss of definition. The indirect method involves covering the fish with a thin sheet of paper or fabric and then applying ink with a tamping or rubbing motion, gradually building up the image. This technique allows for greater control over shading and texture, and is often used for larger or more delicate specimens.

Mastery of gyotaku requires not only technical skill but also a deep understanding of marine biology and traditional Japanese aesthetics. Artists must prepare the fish meticulously, cleaning and positioning it to highlight its natural form. The application of ink is a delicate process, balancing the need for anatomical accuracy with expressive brushwork. Many practitioners also add hand-painted details, such as eyes or background elements, to enhance the lifelike quality of the print. The result is a unique fusion of documentation and artistry, preserving the memory of a specific catch while celebrating the beauty of aquatic life.

Today, gyotaku is recognized as both a cultural heritage and a living art, taught in workshops and exhibited in museums across Japan and internationally. Organizations such as the Government of Japan and the Japan National Tourism Organization promote gyotaku as an important aspect of Japanese traditional arts, ensuring its continued practice and appreciation in the modern era.

Gyotaku in Japanese History: From Fishermen’s Records to Fine Art

Gyotaku, the traditional Japanese art of fish printing, originated in the mid-19th century as a practical method for fishermen to record their catches. The term “gyotaku” is derived from the Japanese words “gyo” (fish) and “taku” (rubbing or impression). According to historical accounts, the earliest known gyotaku prints date back to the Edo period (1603–1868), with the practice becoming more widespread during the subsequent Meiji era. Fishermen would apply sumi ink directly onto the surface of a freshly caught fish, then press washi paper onto the inked fish to create a life-sized, detailed impression. This served as an accurate record of the fish’s size and species, providing both proof of the catch and a memento of the fishing experience.

As Japan modernized and recreational fishing gained popularity, gyotaku evolved from a utilitarian record-keeping technique into a respected art form. Artists began to experiment with colored inks, delicate brushwork, and compositional elements, transforming simple prints into expressive works of art. The transition from monochrome documentation to vibrant, multi-colored prints reflected broader trends in Japanese art, where natural subjects and meticulous attention to detail were highly valued. By the early 20th century, gyotaku was recognized not only as a method of documentation but also as a unique artistic discipline, with practitioners exhibiting their works in galleries and museums.

Today, gyotaku is celebrated both in Japan and internationally as a bridge between science and art. It is used in educational settings to teach about marine biology and fish anatomy, as well as in cultural programs that preserve traditional Japanese crafts. Organizations such as the Government of Japan and various regional museums actively promote gyotaku as part of Japan’s intangible cultural heritage. Contemporary gyotaku artists continue to innovate, incorporating new materials and techniques while honoring the tradition’s roots in the fishing communities of Japan.

The enduring appeal of gyotaku lies in its ability to capture the intricate beauty of marine life with scientific accuracy and artistic sensitivity. As both a historical record and a form of creative expression, gyotaku exemplifies the Japanese appreciation for nature and craftsmanship, ensuring its relevance and vitality well into the 21st century.

Contemporary Artists and Innovations in Gyotaku

In recent years, Gyotaku has experienced a renaissance, with contemporary artists both in Japan and internationally reimagining the traditional practice for modern audiences. While Gyotaku originated as a practical method for recording fishermen’s catches, today it is recognized as a unique art form that bridges natural history, printmaking, and cultural heritage. Contemporary practitioners are expanding the boundaries of Gyotaku through innovative materials, techniques, and conceptual approaches.

Artists such as Naoki Hayashi and Heather Fortner have gained recognition for their detailed and expressive fish prints, often incorporating color, mixed media, and even digital enhancements. These artists emphasize the importance of ethical sourcing, using only fish that have been caught for consumption or found deceased, thus aligning their work with environmental awareness and sustainability. Their prints are not only artistic expressions but also serve as educational tools, raising awareness about marine biodiversity and conservation.

In Japan, organizations like the Japan National Tourism Organization promote Gyotaku workshops and exhibitions, helping to preserve and disseminate the tradition. These events often feature master artists who demonstrate both the direct (chokusetsu-ho) and indirect (kansetsu-ho) methods, and encourage participants to experiment with new materials such as rice paper, silk, and even synthetic fabrics. Some artists have introduced water-based inks and eco-friendly pigments, further modernizing the practice while reducing its environmental impact.

Internationally, Gyotaku has found a following among naturalists, educators, and printmakers. Museums and aquariums, such as the Smithsonian Institution, have incorporated Gyotaku into their educational programming, highlighting its value in both art and science. These institutions often collaborate with artists to create interactive exhibits, where visitors can try their hand at fish printing and learn about the anatomy and ecology of marine species.

Digital technology is also influencing Gyotaku’s evolution. Some artists scan their prints to create high-resolution digital archives or to produce limited-edition giclée prints, making the art form more accessible to a global audience. Social media platforms and online galleries have further expanded the reach of Gyotaku, allowing artists to share their work, techniques, and environmental messages with a worldwide community.

As Gyotaku continues to evolve, contemporary artists are not only preserving a centuries-old tradition but also infusing it with new meaning and relevance. Their innovations ensure that Gyotaku remains a dynamic intersection of art, science, and cultural heritage in 2025 and beyond.

Gyotaku in Museums and Educational Institutions

Gyotaku, the traditional Japanese art of fish printing, has found a significant place in museums and educational institutions worldwide, serving as both a cultural artifact and a hands-on educational tool. Originating in the mid-19th century as a method for fishermen to record their catches, gyotaku has evolved into a respected art form and a valuable resource for teaching about marine biology, art, and Japanese heritage.

Museums in Japan and internationally have incorporated gyotaku into their collections and programming to highlight its historical and artistic significance. Institutions such as the Tokyo National Museum and the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo have displayed gyotaku works, emphasizing their role in documenting biodiversity and traditional practices. These exhibitions often showcase both historical prints and contemporary interpretations, illustrating the evolution of the technique and its relevance to modern audiences.

Educational institutions leverage gyotaku as an interdisciplinary teaching tool. Science museums and aquariums, including the Tokyo Sea Life Park and the Loggerhead Marinelife Center, have hosted workshops where students and visitors create their own fish prints. These activities foster a deeper understanding of fish anatomy, marine conservation, and the importance of biodiversity. By engaging participants in the hands-on process of making gyotaku, educators can bridge the gap between art and science, making learning both interactive and memorable.

Universities and art schools in Japan and abroad have also integrated gyotaku into their curricula. For example, the Tohoku University of Art & Design offers courses that explore traditional Japanese printmaking techniques, including gyotaku, within broader studies of cultural heritage and contemporary art. Such programs encourage students to appreciate the technical skill and cultural context behind the practice, while also inspiring innovation and cross-cultural dialogue.

Furthermore, gyotaku is used in outreach and community engagement initiatives. Museums and educational centers often collaborate with local artists and fishermen to conduct demonstrations and public workshops, preserving the tradition and passing it on to new generations. These efforts not only celebrate Japanese cultural heritage but also promote environmental awareness and stewardship.

Through its presence in museums and educational institutions, gyotaku continues to serve as a bridge between art, science, and culture, ensuring its ongoing relevance and inspiring appreciation for both the natural world and traditional craftsmanship.

Technological Advances: Digital Gyotaku and Preservation

Gyotaku, the traditional Japanese art of fish printing, has experienced a significant transformation in recent years due to technological advances, particularly in digital imaging and preservation techniques. Originally developed in the mid-19th century as a method for fishermen to record their catches, gyotaku involved applying ink directly to the fish and pressing it onto paper or fabric. While this analog process remains valued for its tactile authenticity, the integration of digital technology has expanded both the creative possibilities and the means of preserving these unique prints.

Digital gyotaku employs high-resolution scanners and cameras to capture detailed images of fish, which can then be manipulated using graphic design software. This approach allows artists to experiment with color, layering, and composition in ways that are not possible with traditional methods. Digital tools also enable the creation of gyotaku prints without the need for physical specimens, which is particularly important for the documentation of rare or endangered species. By using digital archives, artists and researchers can share and study gyotaku works globally, fostering collaboration and education across borders.

Preservation of gyotaku has also benefited from technological innovation. Traditional prints, often made on delicate washi paper, are susceptible to fading, tearing, and environmental damage. Digitization provides a means to create permanent records of these works, ensuring their longevity and accessibility for future generations. Museums and cultural institutions in Japan and abroad have begun to digitize their gyotaku collections, making them available through online databases and virtual exhibitions. This not only safeguards the art form but also broadens public engagement and appreciation.

- The National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo and other major Japanese museums have incorporated digital archiving into their conservation strategies, recognizing the importance of preserving both the physical and digital aspects of gyotaku.

- Organizations such as the Japanese Fish Printing Association (Nihon Gyotaku Kyokai) promote the use of digital tools for education and outreach, offering workshops and resources for artists interested in blending traditional and modern techniques.

Looking ahead to 2025, the convergence of digital technology and gyotaku is expected to further enhance the art’s relevance and accessibility. As artificial intelligence and machine learning become more integrated into image analysis, there is potential for automated species identification and ecological data extraction from gyotaku prints, supporting both artistic and scientific endeavors. These advances ensure that gyotaku remains a dynamic and evolving practice, bridging the gap between cultural heritage and contemporary innovation.

Environmental and Conservation Aspects of Fish Printing

Gyotaku, the traditional Japanese art of fish printing, has evolved from a practical method for recording fishing achievements into a celebrated artistic and educational practice. Its environmental and conservation aspects are increasingly recognized, especially as global awareness of sustainable fishing and marine biodiversity grows. Historically, gyotaku was performed by applying ink directly to the bodies of freshly caught fish, then pressing paper or fabric onto the fish to create a detailed impression. While this process originally required the use of real fish, contemporary practitioners and educators have adapted the technique to minimize ecological impact.

One significant environmental consideration is the sourcing of fish for gyotaku. In modern practice, many artists use fish that have already been caught for consumption, ensuring that the printing process does not contribute to overfishing or unnecessary harm to marine life. Some artists and institutions have adopted the use of reusable molds or silicone replicas, which allow for repeated printing without the need for fresh specimens. This approach supports conservation by reducing the demand for wild-caught fish solely for artistic purposes and helps raise awareness about endangered or protected species.

Gyotaku also serves as a valuable educational tool in promoting marine conservation. Museums, aquariums, and environmental organizations in Japan and internationally have incorporated gyotaku workshops into their outreach programs. These workshops often emphasize the importance of sustainable fishing practices, species identification, and the ecological roles of various fish. By engaging participants in hands-on art-making, gyotaku fosters a deeper appreciation for aquatic biodiversity and the need to protect marine habitats. For example, the Tokyo Zoological Park Society and similar organizations have used gyotaku to connect visitors with conservation messages and local marine life.

- Gyotaku can document the presence and size of fish species in specific regions, providing informal records that may support citizen science and local conservation efforts.

- Artists and educators often highlight the importance of respecting catch limits and avoiding threatened species, reinforcing responsible fishing ethics.

- Some gyotaku exhibitions and projects collaborate with marine research institutes to raise awareness about declining fish populations and the impact of human activity on ocean ecosystems.

As gyotaku continues to gain popularity worldwide, its environmental and conservation aspects are likely to become even more integral to its practice. By blending art, science, and environmental stewardship, gyotaku not only preserves a unique cultural tradition but also contributes to the ongoing dialogue about sustainable interaction with the natural world.

Global Spread: Gyotaku’s Influence Beyond Japan

Gyotaku, the traditional Japanese art of fish printing, has evolved from its origins as a practical method for recording fishermen’s catches in 19th-century Japan to a globally recognized art form. Its spread beyond Japan began in earnest during the late 20th century, as international interest in Japanese culture and printmaking techniques grew. Today, gyotaku is practiced and exhibited worldwide, influencing artists, educators, and marine biologists across continents.

The global dissemination of gyotaku can be attributed to several factors. Japanese emigrants and cultural exchange programs introduced the technique to new audiences, while traveling artists and exhibitions further popularized the practice. In the United States, gyotaku gained traction among both artists and scientists, particularly in coastal regions with strong fishing traditions. Museums and aquariums, such as the Smithsonian Institution and the Monterey Bay Aquarium, have featured gyotaku in educational programs and exhibitions, highlighting its dual value as both art and scientific record.

Gyotaku’s influence is evident in the way it bridges art and science. Marine biologists and educators use gyotaku to teach about fish anatomy, biodiversity, and conservation, making the technique a valuable tool for environmental education. Organizations such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the United States have incorporated gyotaku into outreach activities, fostering appreciation for marine life and traditional Japanese culture.

Artists outside Japan have adapted gyotaku to local contexts, experimenting with different species, materials, and styles. In Europe, Australia, and South America, gyotaku workshops and exhibitions are increasingly common, often organized in collaboration with local art institutions and environmental groups. The technique’s accessibility—requiring minimal equipment and allowing for direct engagement with natural specimens—has contributed to its popularity among amateur and professional artists alike.

The global spread of gyotaku has also led to the formation of international networks and societies dedicated to the practice. These communities facilitate the exchange of techniques, ideas, and cultural perspectives, ensuring that gyotaku continues to evolve while honoring its Japanese roots. As of 2025, gyotaku stands as a testament to the enduring power of traditional arts to transcend cultural boundaries and inspire new generations worldwide.

Market Trends and Public Interest: Growth and Forecasts

Gyotaku, the traditional Japanese art of fish printing, has experienced a notable resurgence in global interest, driven by a combination of cultural appreciation, environmental awareness, and the growing popularity of experiential and sustainable art forms. As of 2025, market trends indicate that Gyotaku is evolving from a niche practice among anglers and marine biologists into a broader artistic and educational movement.

In Japan, Gyotaku remains closely tied to its origins as a method for fishermen to record their catches, but it has also been embraced by contemporary artists and educators. Museums and cultural institutions, such as the Tokyo National Museum, have featured Gyotaku in exhibitions, highlighting its historical and artistic significance. This institutional support has contributed to increased public interest and participation in workshops and demonstrations, both domestically and internationally.

Globally, the spread of Gyotaku has been facilitated by art schools, environmental organizations, and marine research centers. For example, the Smithsonian Institution in the United States has incorporated Gyotaku into educational programs to promote marine conservation and biodiversity awareness. Such initiatives have helped position Gyotaku as a tool for environmental education, aligning with broader trends in sustainability and nature-based learning.

The commercial market for Gyotaku art and related materials is also expanding. Art supply companies and specialty retailers report increased demand for traditional inks, rice paper, and instructional materials. Online platforms and social media have amplified the visibility of Gyotaku, enabling artists to reach global audiences and sell original prints or offer virtual workshops. This digital expansion is expected to continue, with forecasts suggesting steady growth in both the number of practitioners and the market value of Gyotaku-related products through 2025 and beyond.

- Rising interest in eco-friendly and hands-on art forms is driving Gyotaku’s popularity among younger demographics.

- Collaborations between artists and marine conservation groups are fostering new applications for Gyotaku in science communication and citizen science projects.

- International art festivals and cultural exchange programs are increasingly featuring Gyotaku, further boosting its global profile.

Looking ahead, the Gyotaku market is forecasted to benefit from continued integration into educational curricula, increased tourism-related activities, and the ongoing digitalization of art experiences. As public interest in traditional crafts and environmental stewardship grows, Gyotaku is well-positioned to remain a vibrant and evolving art form in 2025 and beyond.

Future Outlook: Sustainability, New Media, and Evolving Practices

The future of Gyotaku—the traditional Japanese art of fish printing—reflects a dynamic interplay between sustainability, technological innovation, and evolving artistic practices. As environmental awareness grows globally, practitioners and institutions are increasingly focused on sustainable sourcing and ethical considerations. Many contemporary Gyotaku artists now use fish that are responsibly caught, already destined for consumption, or even create prints from silicone replicas to avoid unnecessary harm to marine life. This shift aligns with broader conservation efforts and the promotion of responsible fishing, as advocated by organizations such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), both of which emphasize sustainable fisheries management and marine biodiversity protection.

Technological advancements are also shaping the future of Gyotaku. Digital media and high-resolution scanning now allow artists to preserve, reproduce, and share their works globally without the need for physical fish or traditional materials. This digital transformation not only broadens the accessibility of Gyotaku but also enables new forms of creative expression, such as interactive online exhibitions and augmented reality experiences. Museums and cultural institutions, including the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, have begun to digitize their Gyotaku collections, making them available to a worldwide audience and fostering cross-cultural appreciation.

Evolving practices within the Gyotaku community reflect a blend of tradition and innovation. While some artists remain dedicated to the classical direct-printing method, others experiment with mixed media, incorporating painting, photography, and digital manipulation. Educational programs and workshops, often supported by local fisheries and environmental groups, are introducing Gyotaku to new generations, emphasizing both its artistic value and its role in marine education. This educational aspect is particularly significant in Japan, where Gyotaku is used to teach children about fish species, anatomy, and the importance of ocean stewardship, echoing the educational missions of organizations like the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan.

Looking ahead to 2025 and beyond, Gyotaku is poised to remain a vibrant and evolving art form. Its integration of sustainability, new media, and educational outreach ensures its relevance in contemporary society, while its deep cultural roots continue to inspire artists and audiences worldwide.

Sources & References

- Japan Foundation

- Japan National Tourism Organization

- Smithsonian Institution

- Tokyo National Museum

- National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

- Tokyo Sea Life Park

- Tohoku University of Art & Design

- Monterey Bay Aquarium

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan